I have many pet peeves, but I reserve a special degree of scorn for one in particular; the laser pointer.

I hate them, and not just because a high school student once caused a complete meltdown in my class, while I was writing on the board, by shining the red dot on my backside, nor because they invariably bounce all over the screen as the speaker tries to aim the dot at a specific point on the slide, leaving me more confused than ever about what he was trying to point out.

No, I hate them because they tell me that I’m in the hands of a presenter who is lazy, incompetent or unprepared.

The only reason for a speaker to ever use a laser pointer in a presentation is if it isn’t clear what part of their slide they are talking about. That can only happen if the slide is overloaded, ill-conceived or badly designed.

If the speaker had taken the time to think through what the relevant and important points were going to be, and to make a separate slide highlighting each point, there would be no need to use the laser pointer.

If the speaker had given enough thought to clearly labeling the graphics, diagrams or images, there would be no need to chase the red dot around the screen.

If the speaker had made the effort to get feedback on what parts of the presentation were likely to be confusing, and taken steps to make them clear, there would be no need to point anything out.

The red dot of shame is nothing more than an admission of failure.

So please, do us all a favor. Put your laser pointer on a hard, concrete surface, place the heel of your boot on top of it and grind it into dust.

If nothing else, use it for its only legitimate and proper purpose; entertaining your cat. At least, the cat will enjoy it.

{ 0 comments }

The coach, Tim Hart, knows his business and he had a lot of very perceptive comments and helpful tips to offer. He began throwing out suggestions, telling Moore to take off his hat, to make eye contact, to stand still, not to begin with “So,..”, to put more drama in his voice, to enunciate better and to separate his words. You could tell from the glassy look in his eyes, Moore was totally overwhelmed.

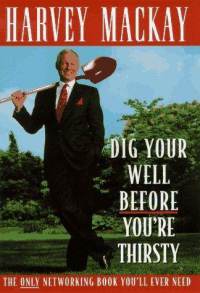

The coach, Tim Hart, knows his business and he had a lot of very perceptive comments and helpful tips to offer. He began throwing out suggestions, telling Moore to take off his hat, to make eye contact, to stand still, not to begin with “So,..”, to put more drama in his voice, to enunciate better and to separate his words. You could tell from the glassy look in his eyes, Moore was totally overwhelmed. The business writer, Harvey Mackay, wrote a book on business networking called, “Dig Your Well Before You’re Thirsty”. That also strikes me as good advice for anyone who expects to be put in the situation of giving high-stakes, high-pressure business presentations.

The business writer, Harvey Mackay, wrote a book on business networking called, “Dig Your Well Before You’re Thirsty”. That also strikes me as good advice for anyone who expects to be put in the situation of giving high-stakes, high-pressure business presentations.